When a pharmaceutical company wants to prove that a generic drug works just like the brand-name version, they don’t test it on thousands of people. They use a smarter, leaner method called a crossover trial design. This isn’t just a statistical trick-it’s the backbone of how regulators like the FDA and EMA decide if a generic drug is safe and effective enough to hit the market. And it’s used in nearly 9 out of 10 bioequivalence studies today.

Why Crossover Designs Rule Bioequivalence

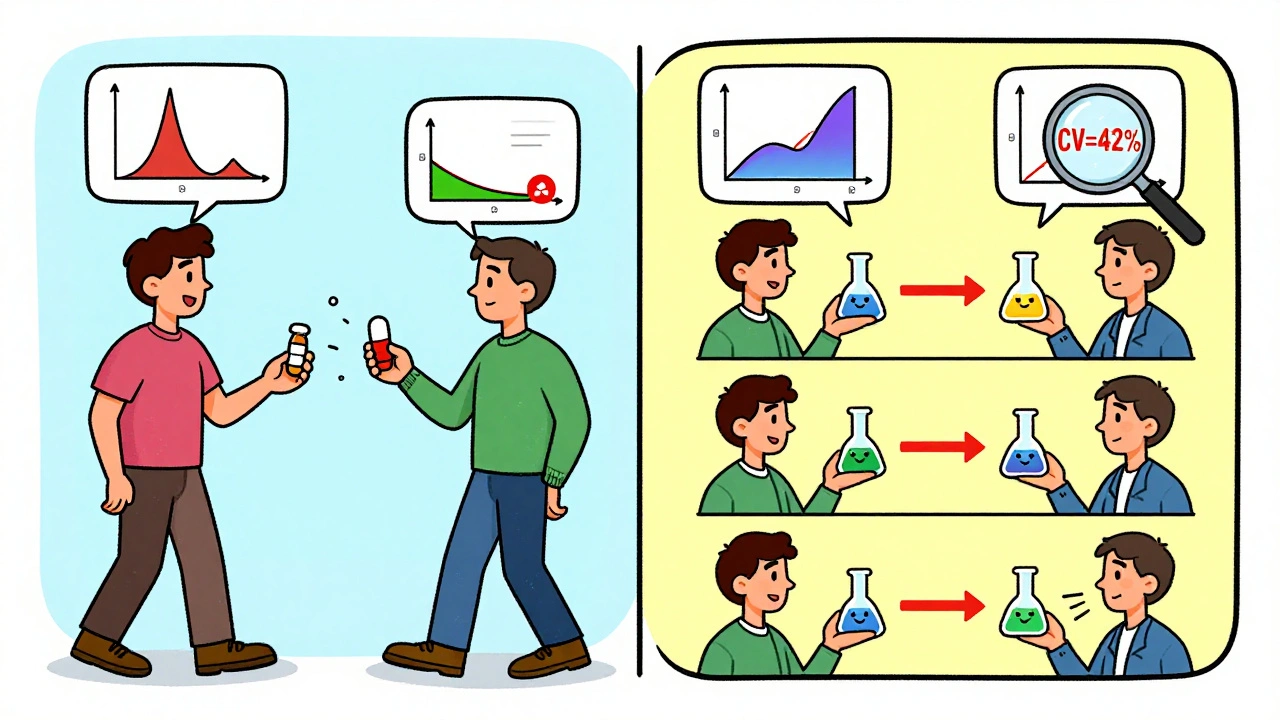

Imagine you’re testing two different painkillers. In a normal study, you’d give one group Drug A and another group Drug B, then compare average results. But people are different-some metabolize drugs faster, some are heavier, some have other health conditions. That noise makes it hard to tell if the drugs are truly different or if it’s just the people. A crossover design fixes that. Each person gets both drugs, one after the other. You’re not comparing John to Mary-you’re comparing John before and after. That cuts out most of the random noise between people. The result? You can get the same statistical power with as few as 12 people instead of 72. That’s a six-fold reduction in sample size when between-person differences are high. This efficiency isn’t theoretical. In 2022, a generic warfarin study saved $287,000 and eight weeks by using a crossover design instead of a parallel group study. The reason? With an intra-subject coefficient of variation (CV) of 18%, only 24 participants were needed. A parallel design would have required 72.The Standard Setup: 2×2 Crossover

The most common structure is the 2×2 crossover. Here’s how it works:- Participants are split into two groups randomly.

- Group 1 gets the test drug first (T), then the reference drug (R) after a washout.

- Group 2 gets the reference drug first (R), then the test drug (T).

What Happens With Highly Variable Drugs?

Not all drugs behave the same. Some, like warfarin or clopidogrel, have wide swings in how they’re absorbed from person to person. Their intra-subject CV can hit 40% or higher. For these, the standard 2×2 design doesn’t cut it. The confidence intervals become too wide, and regulators can’t be sure the drugs are equivalent. That’s where replicate designs come in. These use four treatment periods instead of two. There are two main types:- Partial replicate (TRR/RTR): Test drug once, reference drug twice.

- Full replicate (TRTR/RTRT): Both drugs given twice.

Statistical Analysis: It’s Not Just Averages

You can’t just average the blood levels and call it a day. The data needs a mixed-effects model-usually run in SAS using PROC MIXED or in R using the ‘bear’ package. The model checks three things:- Sequence effect: Did the order of drugs matter?

- Period effect: Did time itself change results (e.g., seasonal changes, diet, stress)?

- Treatment effect: Is there a real difference between the test and reference drugs?

When Crossover Designs Don’t Work

Crossover designs aren’t magic. They fail when the drug’s half-life is too long. If a drug takes 3 weeks to clear the body, you can’t wait 15 weeks between doses. That’s not practical for volunteers, and it’s not ethical to keep someone in a clinical unit for months. In those cases, parallel designs are the only option. That means you need way more people-sometimes 5-6 times more-to get the same statistical power. It’s expensive and slow, but it’s the only way. Another problem? Missing data. If someone drops out after the first period, their second result is gone. That breaks the whole “self-controlled” advantage. Statisticians can’t just guess what their second result would’ve been. The data is invalidated.

Real-World Mistakes and Lessons

One statistician on ResearchGate shared a failed study where they used a 2×2 crossover for a drug with 42% intra-subject CV. They assumed a 7-day washout was enough. It wasn’t. Residual drug was still detectable in period two. The study had to be restarted as a 4-period replicate design-at a cost of $195,000 extra. A 2018 review of FDA rejections found that 15% of major deficiencies were due to inadequate washout periods. That’s not a statistical error-it’s a protocol oversight. Many small CROs underestimate this. They rely on literature values instead of measuring actual clearance in their own subjects. On the flip side, companies using Phoenix WinNonlin software with built-in crossover templates have fewer errors. Open-source tools like R’s ‘bear’ package are powerful but require deep statistical knowledge. Most small labs stick with commercial software to avoid costly mistakes.The Future of Crossover Designs

The trend is clear: more complex drugs mean more complex designs. In 2023, the FDA proposed new guidance allowing 3-period replicate designs for narrow therapeutic index drugs-like digoxin or levothyroxine-where even tiny differences can be dangerous. Adaptive designs are also rising. These let researchers look at early results and adjust sample size mid-study. In 2022, 23% of FDA submissions included adaptive elements, up from 8% in 2018. That means fewer failed studies and less wasted money. Experts like Dr. Donald Schuirmann predict crossover designs will remain the gold standard through at least 2035. But as wearable sensors and continuous monitoring tech improve, we might one day track drug levels in real time-eliminating the need for washouts altogether. Until then, the 2×2 and replicate designs are the tools we have.What You Need to Remember

- Crossover designs reduce sample size by up to 80% compared to parallel studies.

- Washout periods must exceed five half-lives-never assume, always measure.

- For drugs with CV >30%, use a replicate design (TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT).

- Always test for carryover effects-sequence-by-treatment interaction matters.

- Statistical analysis requires mixed models, not simple t-tests.

- 89% of FDA-approved generic drugs in 2022-2023 used crossover designs.

What is the main advantage of a crossover design in bioequivalence studies?

The main advantage is that each participant serves as their own control, eliminating inter-subject variability. This means you need far fewer people to detect a real difference between drugs-often six times fewer than a parallel study-while maintaining high statistical power.

Why is the washout period so important in a crossover trial?

The washout period ensures that the first drug is completely cleared from the body before the second drug is given. If any residue remains, it can interfere with the second treatment’s results, creating a carryover effect. This invalidates the study because you can’t tell if the effect comes from the second drug or leftover first drug. Regulators require washout periods of at least five elimination half-lives.

When should a replicate crossover design be used instead of a standard 2×2 design?

A replicate design (TRR/RTR or TRTR/RTRT) should be used when the intra-subject coefficient of variation (CV) for the reference drug exceeds 30%. These designs allow regulators to use reference-scaled average bioequivalence (RSABE), which adjusts the acceptance range based on how variable the drug is. This avoids requiring impossibly large sample sizes for highly variable drugs like warfarin or clopidogrel.

What are the regulatory acceptance limits for bioequivalence?

For most drugs, bioequivalence is accepted if the 90% confidence interval for the ratio of geometric means (test/reference) falls between 80.00% and 125.00% for both AUC and Cmax. For highly variable drugs, regulators may allow widened limits of 75.00% to 133.33% using RSABE, but only if the reference drug’s within-subject variability meets specific thresholds.

Can crossover designs be used for all types of drugs?

No. Crossover designs are unsuitable for drugs with very long half-lives (e.g., over two weeks) because the required washout period would be too long for participants to wait. In those cases, parallel designs are used instead, even though they require many more subjects. Crossover designs are also not recommended for drugs with irreversible effects or chronic conditions where the drug’s effect lasts beyond the washout period.

Clare Fox

December 5, 2025 AT 21:57Kay Jolie

December 6, 2025 AT 03:05Arjun Deva

December 7, 2025 AT 04:54Inna Borovik

December 8, 2025 AT 15:39Jackie Petersen

December 9, 2025 AT 19:52Annie Gardiner

December 11, 2025 AT 00:36Rashmi Gupta

December 12, 2025 AT 16:59Andrew Frazier

December 14, 2025 AT 04:30Kumar Shubhranshu

December 14, 2025 AT 07:32Mayur Panchamia

December 16, 2025 AT 05:49Geraldine Trainer-Cooper

December 16, 2025 AT 14:29Nava Jothy

December 17, 2025 AT 15:24Kenny Pakade

December 18, 2025 AT 01:23