Imagine you’re struggling with depression, and every night you drink to quiet the noise in your head. Or you have schizophrenia, and smoking marijuana feels like the only thing that helps you feel calm. Now imagine being told to see one doctor for your mood and another for your drinking - and that those two teams don’t talk to each other. That’s the reality for most people with co-occurring mental illness and substance use disorders. It’s broken. But there’s a better way: integrated dual diagnosis care.

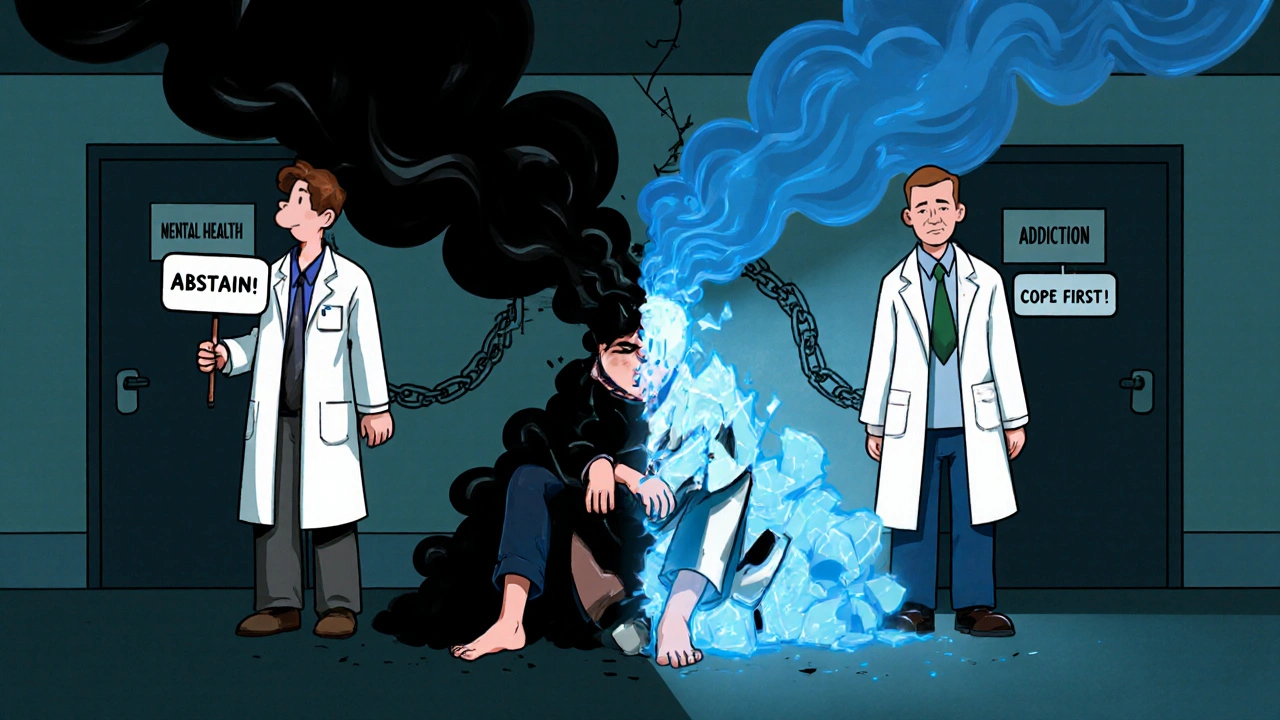

Why Separate Treatments Fail

For decades, the system treated mental health and addiction as two separate problems. If you had depression and drank too much, you’d go to a therapist for your mood and a rehab center for your drinking. But here’s the catch: they didn’t coordinate. One team might push abstinence while the other focused on coping skills. The messages clashed. People got confused. Many dropped out entirely. This isn’t just inefficient - it’s dangerous. Untreated depression can make someone drink more to self-medicate. Heavy alcohol use can trigger panic attacks or worsen psychosis. It’s a loop: one problem feeds the other. Studies show that about 20.4 million U.S. adults live with both a serious mental illness and a substance use disorder. Yet only 6% of them get care that addresses both at the same time. That means over 19 million people are stuck in a system designed to fail them.What Is Integrated Dual Diagnosis Care?

Integrated Dual Diagnosis Treatment (IDDT) is the gold standard for treating people with co-occurring disorders. It’s not a new idea - it was developed in the 1990s by researchers at Dartmouth and New Hampshire. But it’s still rare. IDDT means one team, one plan, one voice. Instead of two separate appointments, you work with a single provider - or a small team - trained to understand both mental illness and addiction. They don’t treat one before the other. They treat them together. That means:- Your therapist knows how your anxiety affects your drug use

- Your case manager understands how your bipolar disorder changes your response to medication

- Your peer support specialist has lived experience with both conditions

The Nine Core Pieces of IDDT

IDDT isn’t just a philosophy - it’s a detailed model with nine proven components. These aren’t optional extras. They’re the building blocks of real recovery.- Motivational interviewing - not pushing change, but helping people find their own reasons to want it

- Substance abuse counseling - focused on reducing harm, even if complete abstinence isn’t possible yet

- Group treatment - peer support with others who get it

- Family psychoeducation - teaching loved ones how to support without enabling

- Participation in self-help groups - like Alcoholics Anonymous or SMART Recovery, adapted for mental health

- Pharmacological treatment - medications for depression, psychosis, or withdrawal, carefully coordinated

- Health promotion - helping people eat better, sleep more, move their bodies

- Secondary interventions - for those who aren’t responding, offering more intensive support

- Relapse prevention - not just avoiding drugs, but recognizing emotional triggers

How It’s Different From Traditional Care

Traditional models follow a sequence: treat the mental illness first, then tackle addiction. Or vice versa. That’s called sequential or parallel treatment. The problem? It ignores reality. If you’re psychotic and using meth, treating your psychosis without addressing the meth use is like putting a bandage on a bleeding artery. The symptoms come back - worse. If you’re in rehab but still hearing voices, you’re likely to walk out. The two conditions are tangled. You can’t untangle them by pulling on one end. IDDT flips the script. It’s not “mental health OR addiction.” It’s “mental health AND addiction.” Same team. Same chart. Same goals. Same language. People don’t get lost between systems. They don’t hear conflicting advice. They get one clear path. A 2019 SAMHSA guide says parallel treatment is “costly, inefficient, and ineffective.” IDDT cuts costs by reducing hospital stays, emergency room visits, and jail time. One study found that for every dollar spent on IDDT, there was a return of about 50 cents in reduced public costs - not a huge profit, but a net gain in human outcomes.Who Delivers IDDT?

This isn’t something any therapist can do. It requires specialized training. Providers need to understand:- How antipsychotics interact with alcohol

- Why someone with PTSD might use cocaine to numb flashbacks

- How bipolar mania can mimic drug intoxication

- When withdrawal symptoms look like psychosis

Why Isn’t Everyone Getting It?

The science is clear. The model works. So why are 94% of people with co-occurring disorders still not getting integrated care? Three big reasons:- Funding - Most insurance systems still pay for mental health and addiction services separately. Integrated programs cost more upfront. Few agencies can afford to restructure.

- Workforce gaps - There aren’t enough clinicians trained in both fields. Mental health counselors often have no training in addiction. Addiction specialists rarely know how to treat schizophrenia or bipolar disorder.

- System fragmentation - Mental health clinics and addiction centers are often in different buildings, run by different agencies, funded by different grants. Getting them to share data, staff, or space is like trying to merge two rival companies.

What Recovery Looks Like

Recovery isn’t about being “cured.” It’s about living better. In IDDT, success looks different for everyone. For Maria, 42, with bipolar disorder and alcohol dependence, success meant going from 12 drinks a week to 2 - and finally sleeping through the night. She still drinks sometimes, but she’s not in the ER anymore. She’s working part-time. She’s seeing her kids. For James, 28, with schizophrenia and cannabis use, success meant reducing his daily smoking from five joints to one, and learning to recognize when his paranoia was worsening. He’s on medication now. He’s in a supported housing program. He’s not homeless anymore. These aren’t perfect outcomes. But they’re real. And they’re possible - only when both conditions are treated together.The Future of Integrated Care

The tide is turning. Medicaid and Medicare are slowly shifting toward value-based payments - paying for outcomes, not just visits. That’s good news for IDDT. When hospitals get paid less for readmissions, they’ll invest in programs that prevent them. Organizations like SAMHSA are pushing states to build infrastructure for integrated care through grants and technical support. More universities are training clinicians in dual diagnosis. Peer support roles are expanding. But progress is slow. The treatment gap is massive. Until funding catches up with the science, thousands will keep falling through the cracks. The message is simple: you can’t fix one without the other. Mental illness and substance use aren’t separate battles. They’re one war - and the only way to win is with a unified front.What is the difference between dual diagnosis and co-occurring disorders?

They mean the same thing. "Dual diagnosis" is an older term that’s still widely used. "Co-occurring disorders" is the more modern, clinical phrase. Both refer to when someone has a mental health condition - like depression, anxiety, or schizophrenia - at the same time as a substance use disorder, such as alcoholism or opioid addiction. The key is that both conditions are active and interacting.

Can you treat addiction without addressing mental illness?

You can try, but it rarely works long-term. If someone has untreated trauma, psychosis, or severe anxiety, they’re far more likely to relapse. Substance use often starts as a way to cope with emotional pain. If that pain isn’t addressed, the person will keep turning to drugs or alcohol - even after rehab. Integrated care treats the root cause, not just the symptom.

Is abstinence required in integrated dual diagnosis care?

No. IDDT uses a harm reduction approach. The goal isn’t always immediate sobriety. It’s reducing the harm caused by substance use. For some, that means cutting back. For others, it means switching from injecting to smoking, or avoiding alcohol when taking psychiatric meds. Abstinence is a goal for many - but it’s not a requirement to start treatment. Progress matters more than perfection.

How long does integrated treatment take?

There’s no fixed timeline. Recovery from co-occurring disorders is often long-term - sometimes years. Many people stay in IDDT programs for 12 to 24 months or longer. The focus isn’t on quick fixes but on building stable routines: consistent medication, healthy sleep, social support, and coping skills. Some people transition to less intensive care after a year. Others need ongoing support for years. That’s normal.

Is IDDT available in New Zealand?

Some services in New Zealand offer integrated care, especially in urban centers like Auckland and Wellington. Public health providers are slowly expanding access through mental health and addiction partnerships. However, availability is inconsistent. Rural areas often lack trained staff and funding. People seeking IDDT should ask their GP or mental health provider for referrals to programs that explicitly treat both conditions together.

What if I’m not ready to change?

That’s okay. IDDT doesn’t require you to be ready to quit. Motivational interviewing - a core part of the model - meets you where you are. The provider’s job isn’t to convince you to change. It’s to help you explore your own reasons for wanting to feel better. Many people start treatment ambivalent and slowly begin to see the connection between their substance use and their symptoms. Change happens over time, not in one moment.

Can family members be involved in IDDT?

Yes. Family psychoeducation is one of the nine core components of IDDT. Loved ones learn how mental illness and addiction affect behavior, how to set healthy boundaries, and how to support without enabling. This reduces conflict at home and helps create a stable environment - which is critical for recovery. Family involvement is optional, but strongly encouraged.

Danny Nicholls

November 22, 2025 AT 21:43Bro this hit different 😭 I’ve seen friends go through the whole ‘see a shrink, then go to AA’ mess and it just… breaks them. One team that gets both? That’s the dream. I wish my county had this.

Robin Johnson

November 23, 2025 AT 20:31Integrated care isn’t optional-it’s ethical. If you’re treating depression without addressing the alcohol dependence, you’re treating symptoms, not people. The data’s clear. Stop pretending it’s too hard.

Latonya Elarms-Radford

November 24, 2025 AT 10:35Let’s be real-this entire system is a grotesque parody of human care. We’ve turned suffering into bureaucratic silos. We treat minds and bodies as if they’re separate entities in a capitalist hellscape where insurance forms matter more than sleep, stability, or sanity. IDDT isn’t just a model-it’s a revolution against the commodification of pain. And yet… we still fund prisons more than therapists. The tragedy isn’t that people fall through the cracks-it’s that we built the cracks on purpose.

Mark Williams

November 25, 2025 AT 06:00From a clinical standpoint, the nine-core framework aligns with evidence-based practice paradigms in transdiagnostic treatment. The emphasis on harm reduction as a non-abstinent entry point is particularly salient in motivational enhancement theory. However, scalability remains constrained by workforce competency gaps and reimbursement fragmentation.

Ravi Kumar Gupta

November 25, 2025 AT 21:49In India, we have zero of this. If you’re depressed and drink, they call you ‘weak.’ If you’re schizophrenic and smoke weed, they lock you up. No one talks about both. We need this. Not just in the US-everywhere.

Rahul Kanakarajan

November 27, 2025 AT 15:17Ugh, another feel-good article. Real talk? Most of these ‘integrated teams’ are just two people sharing a cubicle. They don’t coordinate. They just charge more. Don’t sell me hope-you sell me results.

New Yorkers

November 29, 2025 AT 07:54Look, if you’re not in NYC, you’re not getting this care. We got it here, barely. But in Buffalo? In Albany? Forget it. This is a luxury for the urban elite. The rest of America gets a pamphlet and a prayer.

David Cunningham

November 30, 2025 AT 13:49Been there. Did the whole ‘treat the mental health first’ thing. Took me two years and three relapses to find a team that actually talked to each other. IDDT saved my life. Not because it’s perfect-but because it didn’t pretend I was two separate problems.

luke young

December 2, 2025 AT 08:21Really appreciate how you emphasized harm reduction. So many people think ‘if you’re not sober, you’re not trying’-but that mindset just pushes people away. Progress over perfection, man.

Nikhil Chaurasia

December 3, 2025 AT 19:30My uncle was in a program like this in Kerala. He didn’t stop drinking right away, but he started sleeping. He started talking to his kids again. That’s the win. Not the sobriety. The connection.

Holly Schumacher

December 4, 2025 AT 00:40Correction: It’s not ‘94% of people’-it’s 94.2%. Also, the 2018 trial you cited had a p-value of 0.048, which is barely significant. And you didn’t mention the dropout rate in IDDT programs is still 38%. Let’s not romanticize the data.

Michael Fitzpatrick

December 4, 2025 AT 02:18I’ve been in recovery for 8 years now-bipolar and alcohol. I didn’t get clean until I found a team that knew my meds could make me crave whiskey. That’s the thing no one says: you don’t heal alone. You heal because someone else finally understands how the pieces fit. I still have bad days. But now, I don’t have to hide them. And that? That’s everything.