When you pick up a new prescription, your doctor might say, "This can cause dizziness or nausea." You hear that, and you think: side effect. But what if you get a rash two weeks later? Or your kidneys start acting up? Is that the same thing? The truth is, side effects and adverse drug reactions aren’t interchangeable. Mixing them up can lead to unnecessary fear, wrong decisions, and even dangerous choices-like stopping a life-saving drug because you thought a random headache was a side effect.

What Exactly Is a Side Effect?

A side effect is a known, predictable reaction to a drug that happens because of how the drug works in your body. It’s not a mistake. It’s not an accident. It’s built into the medicine’s design. For example, if you take ibuprofen for a headache, you might get an upset stomach. That’s not a glitch-it’s because ibuprofen blocks enzymes that protect your stomach lining. This is a Type A adverse drug reaction: dose-dependent, predictable, and directly tied to the drug’s pharmacology. About 80-85% of all adverse reactions fall into this category. Side effects show up in clinical trials. Researchers give the drug to one group and a placebo to another. If nausea happens in 20% of the drug group but only 3% in the placebo group? That’s a confirmed side effect. It’s documented. It’s expected. And it’s listed in the patient information leaflet. Common side effects include:- Drowsiness from antihistamines

- Dry mouth from antidepressants

- Diarrhea from antibiotics

- Low blood pressure from blood pressure meds

What Is an Adverse Drug Reaction?

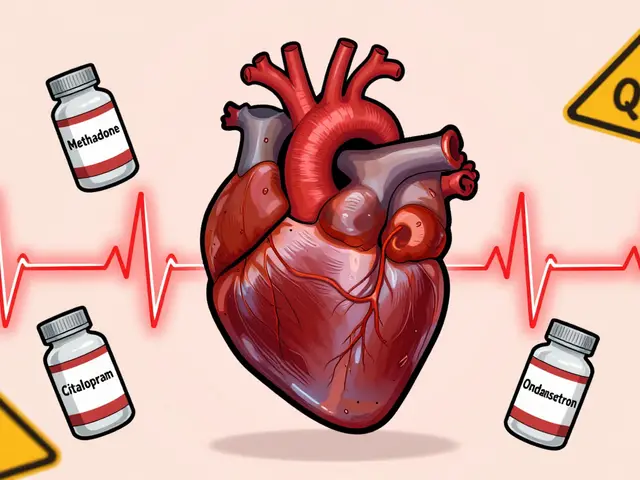

An adverse drug reaction (ADR) is any harmful, unintended response to a medicine taken at normal doses. But here’s the catch: all side effects are ADRs, but not all ADRs are side effects. Type A reactions? Those are your side effects-the predictable ones. But there’s also Type B. These are rare, unpredictable, and not tied to the drug’s main action. They’re like a genetic glitch. Your body reacts in a way no one could have guessed. Think of it this way: if you take penicillin and go into anaphylactic shock, that’s an ADR-but it’s not a side effect. It’s an allergic reaction. It doesn’t happen to everyone. It doesn’t happen at higher doses. It just happens to you, because of your immune system. Other Type B reactions include:- Stevens-Johnson syndrome from allopurinol

- Liver damage from acetaminophen in genetically susceptible people

- Drug-induced lupus from hydralazine

What’s an Adverse Event? (And Why It’s Not the Same)

Now, here’s where things get messy. An adverse event is any negative health occurrence that happens after you take a drug. It doesn’t have to be caused by the drug. Imagine you’re on a blood thinner. One day, you trip and hit your head. You get a concussion. That’s an adverse event. But it’s not an adverse drug reaction. The drug didn’t cause it. You just happened to be taking it when you fell. Or: you start a new cholesterol drug. Two weeks later, you get the flu. Is the drug to blame? Maybe. Maybe not. That’s an adverse event-until proven otherwise. In clinical trials, researchers record every bad thing that happens to every patient. Then they compare rates between the drug group and the placebo group. If headache occurs in 12% of people on the drug and 11.8% on the placebo? It’s not a side effect. It’s just life. The key difference:- Adverse event = Something bad happened after taking the drug. Causality unknown.

- Side effect = Something bad happened, and the data proves the drug caused it.

- Adverse drug reaction = The umbrella term for all harmful reactions-includes both side effects and unpredictable reactions.

Why This Distinction Matters in Real Life

A 2021 survey found that 68% of healthcare workers mix up these terms in their notes. That’s dangerous. If a nurse documents “patient had nausea-side effect of metformin” when it was actually a stomach bug? That’s inaccurate. If a doctor assumes every new symptom is a side effect, they might stop a drug that’s keeping a patient alive. A 2021 study showed 43% of patients stopped taking life-saving medications because they thought every bad feeling was a side effect. One man quit his blood thinner after getting a cold. He had a stroke two weeks later. Proper terminology saves lives. It prevents:- Unnecessary drug discontinuations

- Incorrect insurance claim denials (12% are denied due to mislabeled events)

- Delayed diagnosis of real drug reactions

How Doctors and Pharmacists Tell the Difference

It’s not guesswork. There’s a process. At UCSF, they use a 3-step check:- Temporal relationship-Did the symptom start after the drug was taken? Did it improve when the drug was stopped (dechallenge)? Did it come back when restarted (rechallenge)?

- Known profile-Is this reaction listed in Micromedex or the FDA’s database as a known side effect of this drug?

- Alternative causes-Could it be the flu? Stress? Another medication? A new health condition?

What You Should Do

You don’t need to be a doctor. But you do need to be smart about your meds.- Ask: “Is this a known side effect, or could it be something else?”

- Don’t assume every new symptom is from your drug. Keep a symptom journal: date, time, severity, what else you took.

- If something serious happens-chest pain, swelling, trouble breathing-call your doctor right away. Don’t wait to see if it’s a “side effect.”

- When you get a new prescription, read the patient leaflet. Look for the difference between “common side effects” and “serious adverse reactions.”

- Report bad experiences to the FDA’s MedWatch system. Use “adverse event” if you’re unsure of the cause.

The Bigger Picture

The FDA received 1.2 million adverse event reports in 2023. Only 32% were confirmed as true adverse drug reactions. That means nearly two-thirds of the reports were coincidental, misattributed, or caused by something else. The World Health Organization’s latest drug dictionary now lists over 14,000 confirmed side effects. That’s up from 11,600 just three years ago. Why? Because we’re getting better at telling the difference. Genetic testing is changing the game too. A 2023 study found people with a certain gene variant were 8.7 times more likely to bleed on clopidogrel. That’s not a side effect for everyone. Just for them. Personalized medicine means we’re moving beyond “one-size-fits-all” warnings. The goal isn’t to scare you. It’s to empower you. Knowing the difference between a side effect and an adverse event helps you make smarter choices. It keeps you safe. It keeps your treatment on track.Frequently Asked Questions

Are side effects the same as allergic reactions?

No. Side effects are predictable, dose-related reactions tied to how the drug works in your body. Allergic reactions are immune system responses-unpredictable, not dose-dependent, and can be life-threatening. A penicillin rash or anaphylaxis is an allergic reaction, not a side effect. Both are types of adverse drug reactions, but they’re caused by different mechanisms.

Can a side effect become dangerous over time?

Yes. Some side effects start mild but get worse with long-term use. For example, long-term NSAID use can lead to stomach ulcers or kidney damage. Even if you’ve tolerated the drug for months, your body can change. Always report new or worsening symptoms to your doctor, even if you think it’s just a “side effect.”

Why do drug labels list so many side effects?

Drug labels list all side effects observed in clinical trials-even rare ones-to meet regulatory requirements. Just because it’s listed doesn’t mean you’ll get it. For example, a label might say “1 in 1,000 patients experience hair loss.” That’s rare. But if you’re worried, talk to your pharmacist. They can tell you what’s common, what’s rare, and what’s likely unrelated.

If I have a bad reaction, should I stop the drug immediately?

Only if it’s life-threatening-like swelling of the face, trouble breathing, or chest pain. For milder symptoms, call your doctor first. Stopping suddenly can be dangerous. For example, quitting blood pressure meds or antidepressants abruptly can cause rebound effects. Always get professional advice before stopping any medication.

How do I know if my symptom is a side effect or just bad luck?

Track it. Note when it started, how long it lasts, and if it happens every time you take the drug. Then check: is it listed as a known side effect? Did others in your trial group get it too? If your symptom matches a confirmed side effect and improves when you stop the drug, it’s likely related. If it’s random, or happens even when you skip a dose, it’s probably not.

Eric Healy

November 18, 2025 AT 10:30saurabh lamba

November 19, 2025 AT 19:58Kiran Mandavkar

November 21, 2025 AT 00:56Prem Hungry

November 21, 2025 AT 06:13Leslie Douglas-Churchwell

November 22, 2025 AT 23:01shubham seth

November 24, 2025 AT 00:57Kathryn Ware

November 24, 2025 AT 12:13kora ortiz

November 24, 2025 AT 20:16Jeremy Hernandez

November 25, 2025 AT 16:08Tarryne Rolle

November 26, 2025 AT 23:15Kyle Swatt

November 27, 2025 AT 06:52Deb McLachlin

November 27, 2025 AT 15:14