Ever bought a generic pill and been shocked by the price-only to find your neighbor in the next state paid a third of what you did? It’s not a mistake. It’s not a glitch. It’s the system. In the United States, the same generic drug can cost $12 in one state and $120 in another. And it’s not just about where you live-it’s about who’s controlling the money between the pharmacy and your pocket.

Why the Same Pill Costs Different in Every State

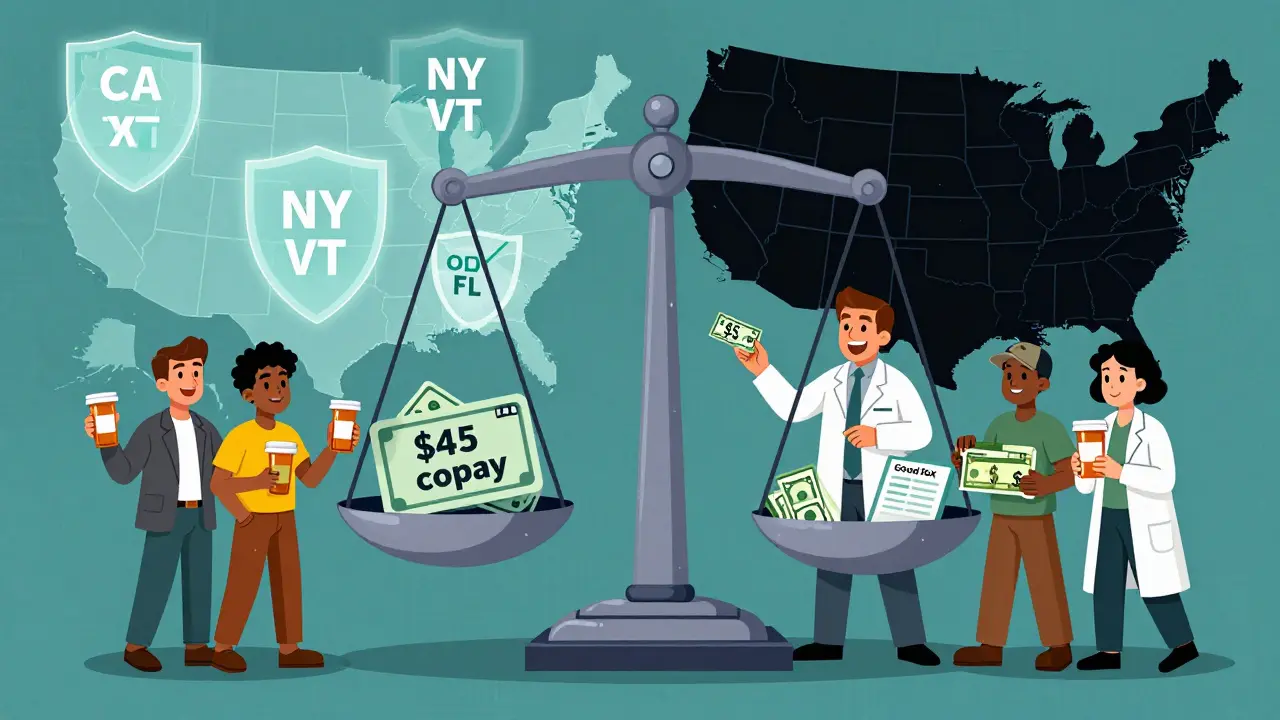

Generic drugs are supposed to be cheap. They’re copies of brand-name medicines, made after the patent expires. No research. No marketing. Just chemistry. So why do they cost so much more in some places? The answer lies in three hidden layers: pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), state Medicaid rules, and how much competition pharmacies face. PBMs are the middlemen between insurers, pharmacies, and drug makers. They negotiate prices, manage formularies, and collect rebates. But here’s the catch: they don’t always pass savings to you. In fact, many PBMs profit from the gap between what they tell insurers they paid for a drug and what they actually paid. That gap? It’s wider in some states than others. States like California and Vermont passed laws requiring PBMs to disclose pricing and ban secret rebates. In those states, patients pay 8-12% less on average for generics. But in states with no transparency laws-like Texas, Florida, or Ohio-those hidden markups stay hidden. And you pay for it.Medicaid Reimbursement Is a Wild Card

Medicaid pays for a huge chunk of generic drugs in the U.S. But each state sets its own reimbursement rate. Some use the National Average Drug Acquisition Cost (NADAC), which updates monthly and reflects what pharmacies actually pay. Others use outdated benchmarks or formulas that don’t match real prices. In states using NADAC, pharmacies get paid fairly. In others? They get paid less than what they paid for the drug. That means pharmacies in those states raise prices for cash-paying customers to make up the difference. And since many generic users are low-income or on fixed incomes, they end up paying more out of pocket. A 2021 study found that wholesale prices for generics were about 45% of the brand-name price a year after launch. But retail prices? They were 66%. That 21-point gap? That’s where the middlemen-PBMs, wholesalers, and pharmacies-take their cut. And that cut varies wildly by state.Competition Matters More Than You Think

If you live in a big city with 10 pharmacies within a mile, you’re likely paying less. More competition drives prices down. But if you live in rural Montana or eastern Kentucky, where there’s only one pharmacy in town? You’re stuck. That pharmacy doesn’t have to compete. So they charge more. GoodRx data from 2022 showed price differences of up to 300% for the same generic drug between neighboring states. In some rural areas, a 30-day supply of metformin cost $15 in one town and $48 in the next county. No change in the drug. No change in the manufacturer. Just geography. Even within states, prices vary. A 2023 analysis of Medicare claims showed that patients in urban areas paid 15-20% less for generics than those in rural areas-even when they had the same insurance.

Cash Beats Insurance (Sometimes)

Here’s the counterintuitive truth: if you’re paying for a generic drug, using your insurance might cost more than paying cash. Why? Because PBMs structure insurance copays to make money, not to save you money. They set copays based on inflated list prices, not actual costs. So if your insurance says your copay for atorvastatin is $45, but the pharmacy’s actual cost is $8-you’re still paying $45. The extra $37? That goes to the PBM. But if you pay cash through GoodRx, Blink Health, or Mark Cuban’s Cost Plus Drug Company? You might pay $4. That’s not a promo. That’s the real cost. In 2020, 4% of all U.S. prescriptions were paid in cash. And 97% of those were for generics. That’s not a coincidence. People figured it out. They realized their insurance wasn’t helping-it was hiding the price.State Laws Are Trying to Fix This (But Getting Blocked)

States aren’t sitting still. Maryland tried to ban price gouging on generics in 2017. Nevada targeted diabetes drug prices. California created a drug price transparency database. But in 2018, a federal court struck down Maryland’s law, saying states can’t regulate prices that cross state lines. That ruling sent a chill through state legislatures. Now, most states focus on transparency-not direct price control. They force PBMs to report rebates. They ban gag clauses that stop pharmacists from telling you about cheaper cash prices. Some even require PBMs to pass savings to consumers. As of 2023, 18 states have created drug affordability review boards. These boards can investigate why prices spike and recommend action. But they can’t set prices. That’s the limit.

What You Can Do Right Now

You don’t need a law change to pay less. You need to know how the system works-and how to game it.- Always check GoodRx before paying. Enter your drug, your zip code, and compare cash prices at nearby pharmacies. Often, the lowest price is at a chain like Walmart or Costco-even if you have insurance.

- Ask for the cash price before you hand over your card. Pharmacists are legally required to tell you. Many won’t volunteer it, but they’ll tell you if you ask.

- Switch to a cash-only pharmacy if you’re on a tight budget. Cost Plus Drug Company, Blink Health, and Blueberry Pharmacy sell generics at wholesale prices with no markup. Shipping is usually free.

- Know your state’s laws. If you live in California, New York, or Maine, you’re protected by stronger transparency rules. Use that. Request pricing reports. File complaints if you’re overcharged.

- Don’t assume insurance is cheaper. For generics, it often isn’t. Paying cash can save you 30-70%.

The Bigger Picture

Generic drugs make up 90% of prescriptions in the U.S. But they account for only 18% of total drug spending. That’s because prices are distorted-not because the drugs are expensive to make, but because the system is rigged. The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 capped insulin at $35 a month for Medicare patients. That’s huge. But it doesn’t help the 68% of Americans who aren’t on Medicare. And even for those who are, the cap doesn’t apply to all generics-just insulin and a few others. The real fix? Break the power of PBMs. Force them to be transparent. Make them pass savings to patients. End secret rebates. Stop letting them profit from confusion. Until then, state-by-state variation isn’t an accident. It’s a feature. And you’re paying for it.How Much Are You Really Paying?

Here’s a quick reality check for common generics:| Drug | Use | Cash Price (Lowest) | Insurance Copay (Avg.) | Savings with Cash |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Atorvastatin (Lipitor generic) | Cholesterol | $4-$8 | $40-$55 | 85-90% |

| Metformin | Diabetes | $5-$10 | $20-$40 | 60-80% |

| Levothyroxine | Thyroid | $7-$12 | $30-$60 | 70-85% |

| Omeprazole | Acid Reflux | $5-$10 | $25-$45 | 70-80% |

| Albuterol Inhaler (generic) | Asthma | $15-$25 | $50-$80 | 60-70% |

Why does my insurance cost more than paying cash for generics?

Your insurance copay is based on a list price set by the pharmacy benefit manager (PBM), not the actual cost of the drug. PBMs often inflate this price so they can collect secret rebates from drug makers. When you pay cash, you bypass the PBM entirely and pay the pharmacy’s real cost-which is often just a few dollars. That’s why cash can be 70% cheaper.

Can my state cap generic drug prices?

No-not directly. In 2018, a federal court ruled that states can’t regulate prices that cross state lines, which blocked laws like Maryland’s ban on price gouging. But states can require transparency, ban gag clauses, and force PBMs to pass savings to patients. So while they can’t set prices, they can make the system less secret.

Are generic drug prices higher in rural areas?

Yes. Rural areas often have only one pharmacy, so there’s no competition to drive prices down. Studies show patients in rural counties pay 15-25% more for generics than those in cities-even with the same insurance. That’s why cash prices and mail-order pharmacies are especially valuable in these areas.

Does the Inflation Reduction Act help with generic drug prices?

Only for Medicare beneficiaries-and only for a few drugs. The law caps insulin at $35 and sets a $2,000 annual out-of-pocket limit for Medicare Part D drugs starting in 2025. But it doesn’t cap prices for non-Medicare patients or affect most generics. For most Americans, it doesn’t change much.

What’s the best way to save on generics right now?

Use GoodRx or a cash-only pharmacy like Cost Plus Drug Company. Always ask for the cash price before using insurance. For most generics, cash is cheaper-even if you have coverage. And if you’re on Medicaid or Medicare, check your state’s rebate rules. Some states pass savings to patients; others don’t.

Martin Spedding

December 17, 2025 AT 00:36bro why is metformin $4 at walmart but $45 with my insurance?? i thought health care was supposed to help?? this system is literally designed to rob people

also i think pbms are just crypto but for pills

Raven C

December 18, 2025 AT 03:24It is, indeed, an egregious manifestation of structural market failure-precisely the kind of systemic dysregulation that arises when profit-maximizing intermediaries are permitted to obfuscate pricing mechanisms under the guise of ‘negotiated rebates.’

One cannot help but note the profound moral hazard inherent in a system wherein the very entities entrusted with cost containment are, in fact, the principal beneficiaries of price inflation.

Furthermore, the notion that patients must ‘game’ the system to access essential therapeutics is not merely inefficient-it is ethically indefensible.

Donna Packard

December 19, 2025 AT 20:47It’s so frustrating to see people struggle with this… but I’m glad there are tools like GoodRx out there. I’ve helped my mom save hundreds just by checking cash prices before using her card. Small wins matter.

Maybe if more people knew, we could slowly change things.

Patrick A. Ck. Trip

December 20, 2025 AT 00:50While the systemic issues described are undeniably complex, it is worth noting that the root cause lies not solely in PBMs, but in the broader absence of federal price regulation and the fragmentation of state-level oversight.

Moreover, the reliance on cash-based alternatives, while pragmatic, is not a sustainable solution-it merely shifts the burden to individuals who lack the time, knowledge, or digital access to navigate these workarounds.

True reform requires standardized, transparent pricing floors, not just consumer hacks.

Apologies for the typos-typing on a tablet in a waiting room.

Jessica Salgado

December 20, 2025 AT 19:11Okay but I just paid $12 for my levothyroxine with insurance… and then I checked GoodRx and it was $8 at CVS? I almost cried.

Why does my pharmacist act like I’m asking for a kidney when I ask for the cash price??

Also-why does my insurance say my copay is $30 when the drug costs $5??

I’m not mad, I’m just… confused. And tired. And scared I’ll miss a dose because I can’t afford it.

Can someone explain this like I’m 12? Because I feel like I’m being scammed by my own healthcare system.

Chris Van Horn

December 22, 2025 AT 02:17You people are clueless. This isn’t about ‘gaming the system’-it’s about the fact that you’re too lazy to understand how supply chains work. PBMs exist because without them, pharmacies would charge $200 for aspirin.

Also, GoodRx? That’s just a middleman with a better marketing team. You think Cost Plus Drug Co. is giving you a discount? They’re undercutting because they don’t pay taxes or comply with state licensing. That’s not ‘fair,’ that’s illegal.

And no-rural pharmacies aren’t ‘marking up.’ They’re the ONLY pharmacy in 50 miles. You think they run on goodwill? Try running a business with $10k in monthly rent and zero competition. Then come back and tell me how ‘evil’ they are.

amanda s

December 22, 2025 AT 21:33AMERICA IS BEING ROBBED. This is why we need to stop letting these corporate scumbags from California and New York tell us how to live. They don’t care about YOU. They care about their bonuses. PBMs are a foreign takeover of our health system.

Why is Canada not having this problem? Why is Germany not having this problem? Because they don’t let greedy CEOs run medicine like it’s a casino.

WE NEED TO BAN PBMS. NOW. AND SEND THEM TO JAIL.

Peter Ronai

December 24, 2025 AT 09:34Everyone here is missing the real issue. You’re all fixated on PBMs and cash prices, but the real villain is the FDA’s archaic approval process for generics. It’s not that prices are high-it’s that there’s not enough competition because the FDA takes 3 years to approve a new generic manufacturer.

And no, GoodRx isn’t magic-it’s just a price aggregator that exploits loopholes in pharmacy contracts. You think the pharmacy is happy to sell you metformin for $5? They’re losing money. Someone else is subsidizing it-probably a nonprofit or a charity that’s running on fumes.

Also, ‘rural pharmacies charge more’? Of course they do. They have to ship drugs 200 miles, pay for 24/7 staffing, and deal with 12% of the patient volume of a city pharmacy. You want lower prices? Move to a city. Or stop pretending rural healthcare is the same as urban healthcare. It’s not. And pretending it is is just elitist nonsense.