Just because a brand-name drug’s patent expires doesn’t mean the cheaper generic version shows up right away. In fact, it often takes years - sometimes more than two - before patients can buy the generic version at a fraction of the price. This isn’t a glitch. It’s the system. And understanding how it works can help explain why some medicines stay expensive long after they should’ve become affordable.

Patent Expiration Isn’t the Finish Line

The 20-year patent clock starts ticking the day a drug company files for protection, not when the drug hits shelves. By the time the FDA approves a new drug - which usually takes 8 to 10 years of testing - most of that patent term is already gone. So even though the patent says it expires in 2026, the company might have had only 7 to 12 years of real market control. That’s why some drugs still cost hundreds of dollars a month even after the patent technically expires.But the real blockers aren’t just patents. The FDA gives extra protection called exclusivity, which can stack on top of patents. A brand-new chemical compound gets 5 years of exclusivity. If the company does new clinical studies for a different use, that adds 3 more years. Orphan drugs - for rare diseases - get 7 years. And if the company tests the drug on kids, they get an extra 6 months. These aren’t loopholes. They’re written into law to encourage innovation. But they also delay generics.

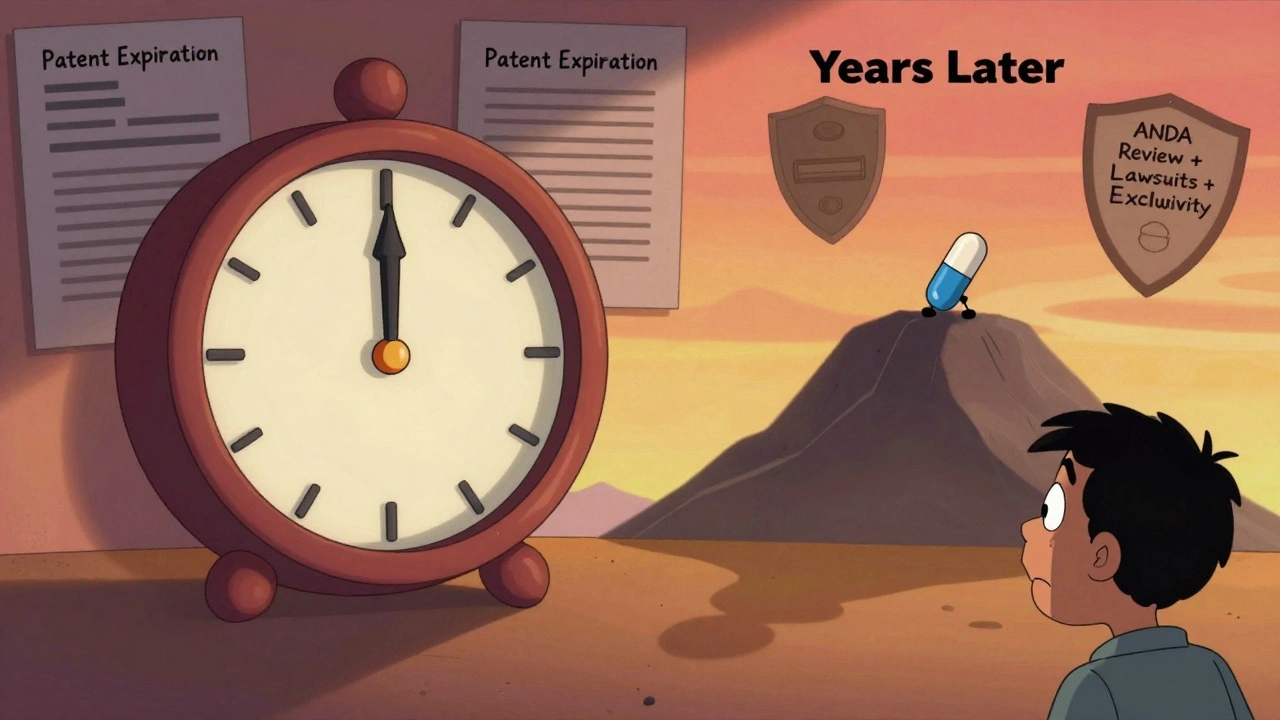

The ANDA Process: Simpler, But Still Slow

Generic makers don’t need to redo all the clinical trials. That’s the point of the Abbreviated New Drug Application (ANDA). Instead, they prove their version is bioequivalent - meaning it works the same way in the body as the brand drug. Sounds easy, right? It’s not.First, the generic company has to wait until all exclusivity periods end. Then they file the ANDA. The FDA’s average review time? About 25 months. That’s over two years just waiting for approval. And if the brand-name company sues, claiming patent infringement, things get messy. Under the Hatch-Waxman Act, that triggers a 30-month automatic delay on approval. Most lawsuits take longer than that to resolve. So even if the patent expired in 2023, the generic might not be approved until 2025.

And here’s the kicker: the FDA can approve the generic, but the company still can’t sell it. Why? Because of other patents - not just on the active ingredient, but on how it’s made, how it’s packaged, even how it’s taken. These are called method-of-use or formulation patents. A single drug can have 10, 15, even 20 listed patents in the FDA’s Orange Book. Generic makers have to challenge each one, or risk getting sued. That’s why some drugs take years longer than others to go generic.

The 180-Day Race and Why It Backfires

The first generic company to successfully challenge a patent gets 180 days of exclusive market access. That’s a huge incentive. It means they can be the only generic seller for half a year, and they often charge a premium during that time - sometimes nearly as much as the brand.But here’s where it gets ugly. To win that exclusivity, the first filer has to launch within 75 days of FDA approval. That’s tight. If their factory isn’t ready, if the drug doesn’t pass quality checks, if there’s a supply issue - they lose the exclusivity. And then everyone else jumps in. The result? A lot of first filers don’t make it. About 22% of them forfeit exclusivity because of manufacturing delays. Another 10% lose it because of court outcomes.

Meanwhile, brand-name companies sometimes settle with the first generic maker - paying them not to launch. These are called reverse payment settlements. The FTC says these cost consumers $3.5 billion a year. In 2021, the Supreme Court ruled such secret deals can violate antitrust law. But they still happen. And they delay generic entry by an average of 2.1 years.

Why Some Drugs Never Go Generic - Or Take Forever

Not all drugs are created equal. Simple pills? Generic versions usually appear within 1.5 years of patent expiration. But complex drugs? That’s a different story.Biologics - drugs made from living cells, like insulin or rheumatoid arthritis treatments - don’t follow the same rules. They need a separate approval path called biosimilars, created by the 2010 Affordable Care Act. The process is longer, costlier, and more complicated. It takes an average of 4.7 years after patent expiry for a biosimilar to launch. And even then, only about 28% of the biologics market is covered by biosimilars today. That’s expected to grow to 45% by 2030, but that’s still a long wait.

Then there’s the “patent thicket” problem. A drug with more than 10 patents listed in the Orange Book sees delays of nearly 2.5 years longer than drugs with just one patent. Cardiovascular drugs? They average 3.4 years of delay after patent expiry. Dermatology drugs? Just 1.2 years. Why? Because heart drugs are high-revenue targets. More money = more patents = more legal fights.

Who’s Winning? Who’s Losing?

The big generic players - Teva, Viatris, Sandoz - control nearly half the U.S. market. They have the resources to fight patent battles, build multiple manufacturing lines, and wait years for approval. Smaller companies? They often can’t afford it. That means fewer competitors, less price pressure, and slower access to low-cost drugs.Meanwhile, patients pay the price. In 2023, generics made up 92% of all prescriptions in the U.S. But they accounted for only 16% of total drug spending. That’s a $373 billion savings for the system. But if generic entry is delayed by a year on a top-selling drug, Medicare alone loses $1.2 billion. That’s money that could go to more patients, better care, or lower premiums.

What’s Changing?

There are signs of progress. The CREATES Act of 2019 stopped brand-name companies from blocking generic makers from getting samples of the drug to test. The Orange Book Transparency Act of 2020 forced companies to list patents more accurately - and it cut patent disputes by 32% in the first year.The FDA is also trying to speed things up. Under GDUFA II, they promised to cut review times for complex generics from 36 months to 24. But as of mid-2024, only 62% of applications met that goal. AI could help. Early tests show it can cut bioequivalence testing time by 25% - which could shave months off development.

Still, the biggest problem remains: patent evergreening. Companies make tiny changes - a new coating, a different pill shape, a slightly different release time - and file a new patent. A 2024 study found that 68% of brand-name drugs get at least one new patent within 18 months of the original expiring. That’s not innovation. That’s delay.

What This Means for You

If you’re waiting for a generic version of your medication, don’t assume it’ll show up the day the patent expires. Check with your pharmacist. Ask if there’s a generic approved by the FDA but not yet on shelves - that happens more often than you think. And if your drug is expensive and still brand-only, it’s likely because of legal delays, not science.The system was designed to balance innovation and access. But today, the balance is tilted. It’s not broken - it’s being manipulated. And until that changes, the gap between patent expiration and real availability will keep patients waiting - and paying more than they should.

Richard Eite

December 9, 2025 AT 09:49Olivia Portier

December 9, 2025 AT 18:12Asset Finance Komrade

December 11, 2025 AT 11:02Jennifer Blandford

December 12, 2025 AT 01:17Delaine Kiara

December 12, 2025 AT 04:29Taya Rtichsheva

December 13, 2025 AT 01:14Mona Schmidt

December 13, 2025 AT 20:34Sarah Gray

December 14, 2025 AT 00:57Michael Robinson

December 14, 2025 AT 14:22precious amzy

December 15, 2025 AT 15:01Carina M

December 15, 2025 AT 23:09Ajit Kumar Singh

December 16, 2025 AT 02:51