When the portal vein - the main blood vessel carrying blood from your intestines to your liver - gets blocked by a clot, it’s not just a minor issue. Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) can lead to life-threatening complications like intestinal ischemia, worsening liver damage, or even death if ignored. Yet, many patients go undiagnosed because symptoms are vague: mild abdominal pain, bloating, or no symptoms at all. The good news? If caught early and treated right, most people recover well. The key is knowing when to suspect it, how to confirm it, and which anticoagulant to use - and when not to use one.

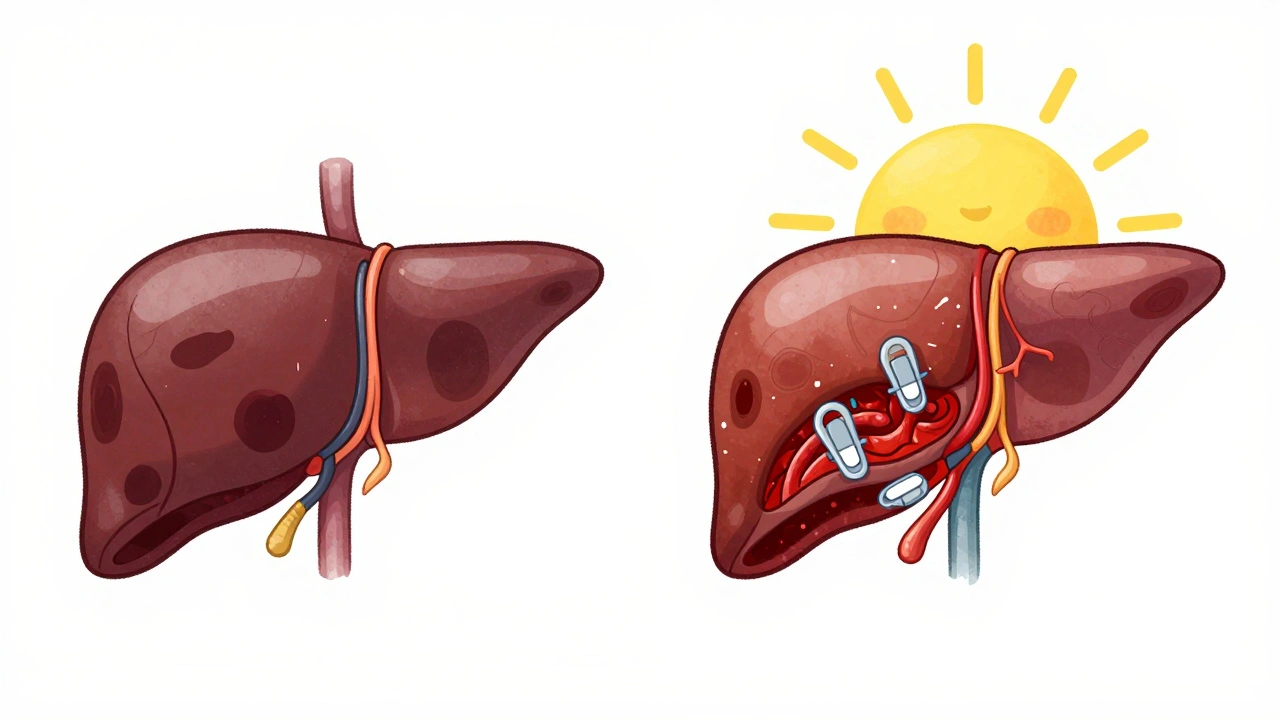

What Exactly Is Portal Vein Thrombosis?

Portal vein thrombosis happens when a blood clot forms in the portal vein or its branches inside the liver. It’s not rare - about 250,000 cases are diagnosed yearly in the U.S., and that number is rising. The clot can be partial or total. In acute cases, the clot is fresh (under two weeks old). In chronic cases, it’s been there for more than six weeks and may have triggered the formation of abnormal collateral vessels around the blocked vein - a condition called cavernous transformation.

What causes it? The triggers vary. In people without liver disease, common causes include inherited clotting disorders (like Factor V Leiden), abdominal infections, recent surgery, or cancer. In those with cirrhosis, the clot often forms because blood flow slows down in a damaged liver, combined with abnormal clotting factors. About 25-30% of non-cirrhotic PVT cases have an underlying thrombophilia - a hidden tendency to form clots.

How Is It Diagnosed?

Ultrasound is the first and most important test. Doppler ultrasound can detect reduced or absent blood flow in the portal vein with 89-94% accuracy. If the ultrasound is unclear, doctors turn to CT or MRI with contrast - these show the clot’s exact location and whether the vein is completely blocked or if collateral vessels have formed.

Doctors classify the clot by how much of the vein it blocks:

- Minimally occlusive: Less than 50% of the vein is blocked

- Partially occlusive: 50-99% blocked

- Completely occlusive: 100% blocked - this is the most dangerous

In chronic cases, the original vein may disappear entirely, replaced by a network of tiny vessels - the hallmark of cavernous transformation. This change makes liver transplants harder, which is why early diagnosis matters so much.

Why Anticoagulation Is the Standard Treatment

For decades, doctors were unsure whether to anticoagulate patients with PVT - especially if they had cirrhosis. But recent data changed everything. Today, major guidelines from the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) and the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) agree: anticoagulation should be started in most acute cases, even in cirrhotic patients, if bleeding risk is low.

The goal isn’t just to prevent the clot from getting bigger. It’s to dissolve it - to restore blood flow. Studies show that patients who start anticoagulation within six months of diagnosis have a 65-75% chance of full or partial recanalization (the vein reopening). If treatment is delayed beyond six months, that drops to just 16-35%.

Without treatment, the risk of intestinal ischemia - where the bowel doesn’t get enough blood - skyrockets. That’s a surgical emergency. Also, untreated PVT makes liver transplant eligibility harder. At UCSF, anticoagulation cut the number of transplant candidates disqualified due to PVT from 22% down to 8%.

Which Anticoagulant Should You Use?

Not all blood thinners are the same for PVT. The choice depends on whether you have cirrhosis, your liver function, kidney health, and bleeding risk.

For Non-Cirrhotic Patients

Direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) are now the first choice. They’re easier to use than warfarin - no regular blood tests, fewer food interactions, and better results.

- Rivaroxaban: 20 mg daily - recanalization rate of 65%

- Apixaban: 5 mg twice daily - 65% recanalization

- Dabigatran: 150 mg twice daily - 75% in small studies

These drugs outperform warfarin, which only achieves 40-50% recanalization. DOACs are especially effective in patients with thrombophilias - the clotting disorders that cause about one in three non-cirrhotic cases.

For Cirrhotic Patients

This is trickier. If you have Child-Pugh class A or B cirrhosis, low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is still preferred. Why? It’s more predictable in liver disease. Warfarin is less reliable because the liver can’t make clotting factors properly.

- LMWH (enoxaparin): 1 mg/kg twice daily or 1.5 mg/kg once daily - recanalization rate of 55-65%

- Warfarin: Target INR 2.0-3.0 - only 30-40% success rate

The 2024 AASLD update now allows DOACs in Child-Pugh B7 patients, based on the CAVES trial showing non-inferior results to LMWH. But DOACs are still avoided in Child-Pugh C - too much risk of bleeding.

When Not to Anticoagulate

Anticoagulation isn’t safe for everyone. Avoid it if:

- You’ve had a variceal bleed in the last 30 days

- You have uncontrolled ascites (fluid in the belly)

- You have Child-Pugh class C cirrhosis

- Your platelet count is below 50,000/μL (unless you get a transfusion first)

In cirrhotic patients, variceal bleeding is the biggest danger. That’s why experts now recommend endoscopic band ligation - a procedure to tie off swollen veins - before starting anticoagulation. At UCLA, this cut major bleeding events from 15% to just 4%.

How Long Should You Stay on Blood Thinners?

It depends on why you got the clot.

- Provoked PVT: If the clot was caused by a temporary trigger like recent surgery or infection, treat for 6 months. Then stop if the cause is gone and the vein reopened.

- Unprovoked PVT: If no clear trigger exists - especially with a thrombophilia - lifelong anticoagulation is recommended.

- PVT with cancer: Treat as long as the cancer is active. Use LMWH or DOACs depending on kidney function and bleeding risk.

For transplant candidates, even if the clot clears, many centers continue anticoagulation until after transplant to prevent recurrence.

What If Anticoagulation Fails?

If the clot doesn’t shrink after 3-6 months of anticoagulation, or if you develop complications like intestinal ischemia, doctors may turn to other options:

- TIPS (Transjugular Intrahepatic Portosystemic Shunt): A metal stent placed inside the liver to bypass the blocked vein. Works in 70-80% of cases but can cause confusion or drowsiness (hepatic encephalopathy) in 15-25% of patients.

- Percutaneous thrombectomy: A catheter is inserted to physically break up the clot. Works in 60-75% of cases but only available at major centers.

- Surgical shunts: Rarely used today due to high complication rates.

These are last-resort options. Anticoagulation still works best for most people - especially when started early.

Real-World Outcomes and Challenges

At Mayo Clinic, 78% of patients who started anticoagulation within 30 days saw improvement. Only 42% did if treatment was delayed. At Cleveland Clinic, 18% of Child-Pugh B patients had to stop anticoagulation because of bleeding - a reminder that balance is everything.

The biggest mistake? Waiting. At Massachusetts General Hospital, patients who presented with bowel ischemia had a 22% death rate. Those treated early? Only 5% died.

Another problem: many primary care doctors and even general gastroenterologists don’t feel confident managing PVT. Only 35% of them say they’re fully competent in choosing the right anticoagulant. That’s why multidisciplinary teams - hepatologists, radiologists, transplant surgeons - are key. Johns Hopkins found that when these teams work together, complications drop by 35%.

The Future of PVT Treatment

Things are changing fast. The FDA approved andexanet alfa in 2023 - a drug that can reverse the effects of rivaroxaban and apixaban in emergencies. That’s a game-changer for bleeding risks.

Also, the 2024 AASLD update now supports DOACs in more cirrhotic patients. And the PROBE trial (2023) showed DOACs are as safe as LMWH in Child-Pugh A/B patients. By 2025, experts predict DOACs will be used in 75% of non-cirrhotic cases and 40% of compensated cirrhotic cases.

On the horizon: new drugs like abelacimab (in phase 2 trials) and targeted thrombolysis. But for now, anticoagulation remains the backbone of treatment.

Getting Started: What You Need to Do

If you or someone you know has been diagnosed with PVT, here’s your action plan:

- Confirm the diagnosis with Doppler ultrasound - and get a CT or MRI if needed.

- Check liver function with Child-Pugh and MELD scores.

- Screen for varices with endoscopy - especially if you have cirrhosis.

- Test for thrombophilia if you’re under 50 and have no obvious cause.

- Start anticoagulation within days if bleeding risk is low.

- Use DOACs if you’re non-cirrhotic; LMWH if you have Child-Pugh A/B cirrhosis.

- Follow up with imaging at 3 and 6 months to check for recanalization.

Don’t wait. Early treatment doesn’t just save your liver - it saves your life.

Can portal vein thrombosis be cured?

Yes, in many cases. With early anticoagulation, 65-75% of patients achieve partial or complete recanalization - meaning the clot dissolves and blood flow returns. The chances drop sharply if treatment is delayed beyond six months. In non-cirrhotic patients, especially those with thrombophilias, long-term or lifelong anticoagulation may be needed to prevent recurrence.

Is anticoagulation safe for people with cirrhosis?

It can be, but only if the cirrhosis is compensated (Child-Pugh A or B). In these patients, LMWH is preferred over warfarin or DOACs because it’s more predictable. DOACs are now approved for Child-Pugh B7 patients based on recent trials. But anticoagulation is dangerous in Child-Pugh C cirrhosis - the risk of bleeding, especially from varices, is too high. Always screen for esophageal varices and treat them with band ligation before starting anticoagulation.

What are the signs that PVT is getting worse?

Watch for sudden, severe abdominal pain, especially after eating; fever; nausea or vomiting; bloody stools; or worsening ascites. These can signal intestinal ischemia - when the bowel doesn’t get enough blood. This is a medical emergency. Also, if you develop confusion, drowsiness, or slurred speech, it could mean the clot is affecting liver function or causing hepatic encephalopathy. Don’t wait - get checked immediately.

Do I need to avoid certain foods or supplements while on anticoagulants?

If you’re on warfarin, you need to keep vitamin K intake consistent - found in leafy greens like spinach and kale. Sudden changes can affect your INR. But if you’re on a DOAC like rivaroxaban or apixaban, no dietary restrictions are needed. Avoid herbal supplements like St. John’s wort, ginkgo, or high-dose fish oil - they can increase bleeding risk. Always tell your doctor what supplements you’re taking.

Can I still get a liver transplant if I have PVT?

Yes - but only if the clot is treated. Untreated PVT often disqualifies patients from transplant lists. Anticoagulation improves recanalization and increases transplant eligibility. Studies show that anticoagulated patients have an 85% one-year survival rate after transplant, compared to 65% for those who weren’t treated. Many transplant centers now require anticoagulation before listing.

How often do I need imaging tests after starting treatment?

You’ll typically have a follow-up Doppler ultrasound at 3 months to see if the clot is shrinking. Another scan at 6 months confirms whether recanalization occurred. If the clot is gone and you have a provoked cause, your doctor may stop anticoagulation. If it’s still there or you have a thrombophilia, you’ll likely continue treatment longer - possibly lifelong. Imaging is key to knowing if treatment is working.

James Moore

December 4, 2025 AT 22:58Let me tell you something - this country used to produce real science, not this watered-down, corporate-approved medical dogma. They're pushing DOACs like they're energy drinks, and nobody's asking: what about the long-term endothelial damage? What about the silent microbleeds accumulating over years? We're turning patients into chemical experiments while the FDA collects its licensing fees. And don't get me started on how they've turned anticoagulation into a one-size-fits-all algorithm - as if the human body runs on a spreadsheet! The truth? We've forgotten how to heal - we just manage symptoms until the next patent expires.

Chris Brown

December 6, 2025 AT 03:56It is, frankly, irresponsible to suggest that anticoagulation should be initiated in cirrhotic patients without first establishing absolute certainty regarding variceal status. The data cited, while statistically compelling, ignores the fundamental ethical imperative: first, do no harm. To expose a patient with Child-Pugh B cirrhosis to the risk of gastrointestinal hemorrhage - even if the probability is reduced - is to prioritize statistical optimism over clinical prudence. The guidelines, in their haste to appear progressive, have sacrificed the bedrock of medical ethics.

Laura Saye

December 6, 2025 AT 23:36I just want to say how much I appreciate the nuance here. It’s easy to get lost in the numbers - recanalization rates, DOACs vs LMWH - but what really matters is the human story behind each clot. I’ve seen patients who were terrified to start anticoagulants because they thought it meant they were ‘broken.’ But when they understood it wasn’t about weakness, but about restoring flow - literally and metaphorically - something shifted. It’s not just medicine. It’s dignity. Thank you for framing this with both precision and humanity.

Krishan Patel

December 7, 2025 AT 03:12Are you kidding me? You're recommending DOACs for non-cirrhotic patients like they're over-the-counter aspirin? Have you even read the real literature? The CAVES trial was funded by pharmaceutical giants with vested interests in replacing LMWH. And you call this science? In India, we still use warfarin because we can monitor it - not because we're backward, but because we're practical. You Western doctors think you're saving lives, but you're just selling pills. And now you're exporting your arrogance along with your drugs.

Carole Nkosi

December 7, 2025 AT 06:47Let’s be real - this whole system is a scam. They tell you ‘early treatment saves lives,’ but who gets early treatment? People with insurance. People who can afford the CT scans, the follow-ups, the specialist visits. Meanwhile, the uninsured sit in waiting rooms with bloated bellies and silent clots, dying quietly because no one told them to ‘get checked.’ This isn’t medicine. It’s a luxury service wrapped in jargon. They don’t want to cure PVT - they want to monetize it.

Mark Curry

December 8, 2025 AT 06:27Really helpful breakdown. I’ve been following this since my cousin got diagnosed last year - didn’t know about the 6-month window being so critical. Glad to see DOACs are working better than warfarin. Still nervous about bleeding risks, but this gives me hope. 😊

Manish Shankar

December 9, 2025 AT 22:26With profound respect for the meticulous analysis presented herein, I would like to respectfully submit that the temporal threshold of six months for initiating anticoagulation may require further stratification based on etiological subtypes. Specifically, in patients with inherited thrombophilias presenting with partial occlusion, earlier intervention - even within 14 days - may yield superior recanalization outcomes, as suggested by preliminary data from the Mumbai Hepatic Cohort Study (2022). The current guidelines, while commendable, may benefit from granular temporal refinements.

Rupa DasGupta

December 11, 2025 AT 04:45Wait - so if I’m cirrhotic and I have a clot, I’m supposed to get band ligation BEFORE the blood thinner? But what if I’m too scared to get the endoscopy? 😭 I mean, I’ve seen videos of those bands… I’d rather just die slowly than go through that. Also, why does everyone act like DOACs are magic? I took rivaroxaban and my gums bled for a week. No one warned me. 😤

Marvin Gordon

December 12, 2025 AT 09:20This is exactly why we need more hepatology-trained primary docs. I’m a nurse practitioner in rural Ohio - I see 3 patients a month with vague abdominal pain. If I don’t think of PVT, they get sent home with antacids. Then they show up in ER with ischemia. This post? It’s a lifeline. Share it with your PCPs. We’re not specialists - but we can learn. And we should.